News of the killing of George Floyd and several other Blacks in the summer of 2020 initiated protests, marches, demonstrations and an awakening of social justice throughout the country. Piedmonters of all ages marched through town to show their support for social justice. Piedmont residents began to learn about Piedmont’s racist history, and the story of Sidney Dearing, long forgotten, came to light.

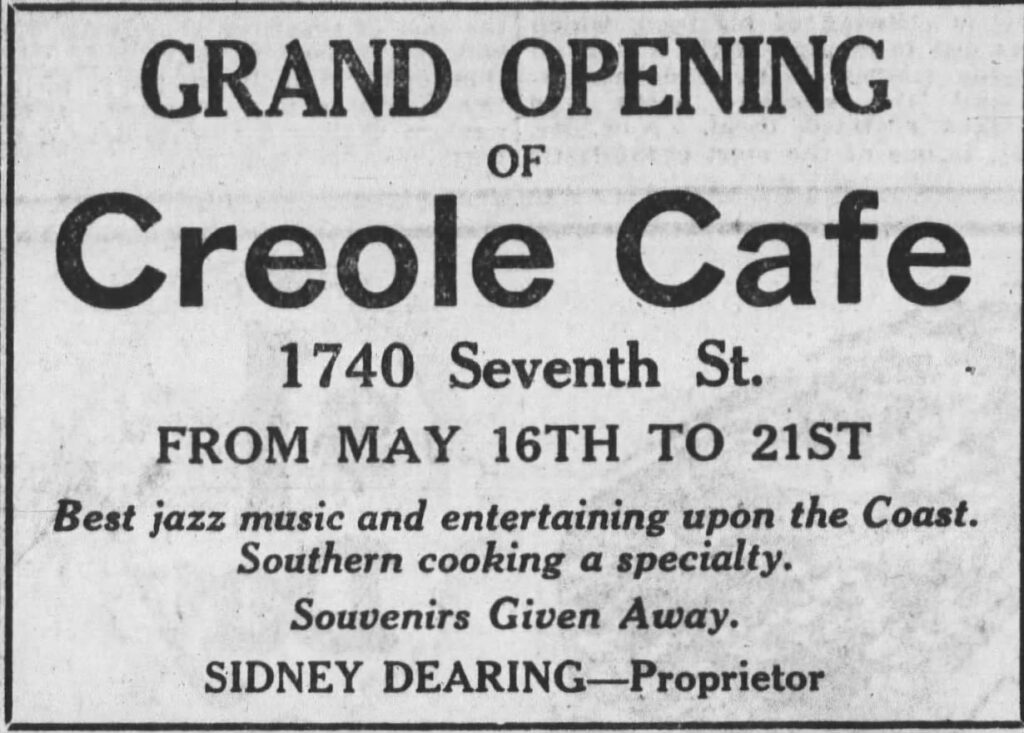

Sidney Dearing was a successful Black businessman who owned a jazz club on 7th Street in West Oakland. He was born in Texas in 1870 and arrived in Oakland in 1907. By 1918, he was the proprietor of the popular Creole Café which featured New Orleans-style jazz, big-band music and Southern cooking. The Café prospered until 1921 when police revoked its liquor license for selling liquor during Prohibition (1920-1933).

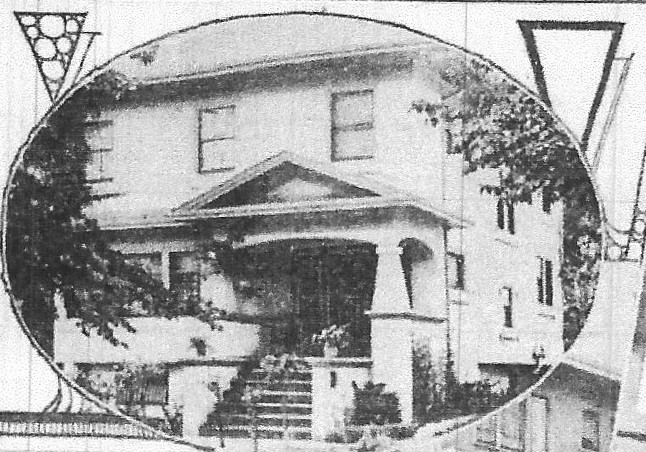

On January 21, 1924, Sidney Dearing and his wife, Irene, bought the house at 67 Wildwood Avenue in Piedmont. Irene’s mother purchased the house with Sidney’s money for a reported $10,000. She told the seller she was French Canadian hereby circumventing racial restrictions. The Oakland Tribune published the photo below of Dearing’s house on June 4, 1924.

When Piedmont residents discovered that Sidney was Black, they wanted him to leave Piedmont. On March 14, 1924, the Piedmont Weekly News reported that residents protested to the Piedmont City Council the sale of the house to colored. The original deed for the house at 67 Wildwood Avenue had a clause prohibiting the sale to “any other than whites,” but the clause was said to have expired in 1923. The City Council was powerless to act and replied that it was a neighborhood matter. The Council suggested that the residents cooperate to buy Dearing out. Dearing soon began receiving letters demanding that he either sell or move away and rent his house to white people. Dearing refused.

Piedmont Police Chief Burton Becker was a high-ranking member of the local Ku Klux Klan and did not provide adequate protection for Dearing. The Alameda County Sheriff called in two deputies to guard the Dearing house. Dearing’s wife and two young daughters moved back to West Oakland, and Dearing hired five additional Blacks to protect himself and his house.

Residents continued to demand that Dearing sell, and Dearing continued to refuse to sell. Handbills were posted around town calling for a meeting. The Piedmont Weekly News reported the gathering. On May 6, at 8 pm, a crowd of 500 Piedmont residents gathered in front of Dearing’s house and demanded that he sell his house and leave Piedmont. Dearing agreed to meet in one week to discuss arrangements for the sale of his house, and the crowd dispersed. It was the first time that Dearing had agreed to discuss the sale of his house.

At the meeting one week later, Dearing was asked whether he had set a price. Dearing replied that he had not. The representatives from the neighborhood stated that was all they wanted to know and left. Later Dearing stated, “I wouldn’t sell the house under peaceful conditions for less than $15,000. Statements vary as to whether Dearing paid $10,000 or $10,500 for his house.

In a letter dated May 16, City Attorney Girard Richardson, writing on behalf of the Piedmont city Council, offered Dearing $8,000 for his property on Wildwood and requested that he leave the city. If that offer was not accepted immediately, the city would start condemnation proceedings to acquire the property for public use.

Dearing refused the offer of $8,000. In a letter on Dearing’s behalf attorney John D. Drake, president of the Northern California branch of the NAACP, claimed the following:

“If the City of Piedmont can hide behind the flimsy subterfuge of a public necessity that does not exist and act to naught [disregard] the constitutional rights of an American citizen and take away his property, simply on the ground of his color, so may the constitutional rights of any American citizen be set at naught [disregarded] when he shall incur the displeasure of his more powerful associates…”

John D. Drake

Attorney for Sidney Dearing

When Dearing refused to accept the city’s offer of $8,000 for his house, Piedmont City Council passed a resolution to condemn Dearing’s property and the property behind it at 48 Fairview and to build a street between Wildwood and Fairview Avenues. On May 30, the Piedmont Weekly News published Mayor Ellsworth’s statement: “The question of building a street at this point has been considered for some time…The council has received many suggestions during the past two years that a street be built at this point.”

In the ensuing weeks, bombs were found on or near Dearing’s property. On June 1, a bomb was found in the shrubbery of Dearing’s neighbor. Police did not know if it was intended for Dearing’s property or that of his neighbor who was supporting Dearing’s ouster. One bomb was thrown from a passing car. On June 5th, the Oakland Tribune announced that Dearing found a third bomb on his lawn. The fuse was sputtering. Dearing stomped it out and ran around the corner of his house for protection. When he returned to inspect the bomb, it was gone.

While the city prepared its condemnation case against Sidney Dearing, the Piedmont Weekly News reported on June 13, that Dearing moved his entire family back into his home at 67 Wildwood. In addition to his wife Irene and their two small children, Irene’s mother Julia Davis also moved into the house. Mrs. Davis was the original purchaser of the house. When interviewed, Mrs. Davis stated, “Mr. Dearing will not move until he gets his price… we are all living here again.” The Oakland Tribune reported that Dearing was maintaining an armed guard at his house, and the police were keeping an officer on duty at the house. At this time, Mayor Ellsworth expressed his opinion that Dearing would not let the case go to court, and that the City would pay Dearing the appraised value of the property.

On August 15, the Piedmont Weekly News reported that the City of Piedmont prevailed in the first hearing against Sidney Dearing. Attorney Drake filed three objections to the complaint, and Judge John D. Murphy overruled each. Piedmont City Attorney Richardson asked for a September 15 trial date.

At the second court hearing in Piedmont’s condemnation suit against Dearing, attorney Drake charged conspiracy between the Piedmont City Council and residents. Drake was again overruled. Drake then asked that the property be appraised and that the court set a fair price for Dearing’s house. City Attorney Richardson agreed.

At the third hearing on Friday, Oct 10, Dearing claimed that the condemnation was a move to force him from Piedmont rather than a move to cut a street through his property. Piedmont City Attorney Richardson replied that the action of the City Council was made on a two-thirds vote and that the council has the power to condemn property for public work. He added that the residents of the neighborhood had asked for a street there for many years. The judge upheld Richardson’s reply.

The condemnation suit was continued until October 31, to determine whether a municipality like Piedmont must state the purpose for the condemnation of a property.

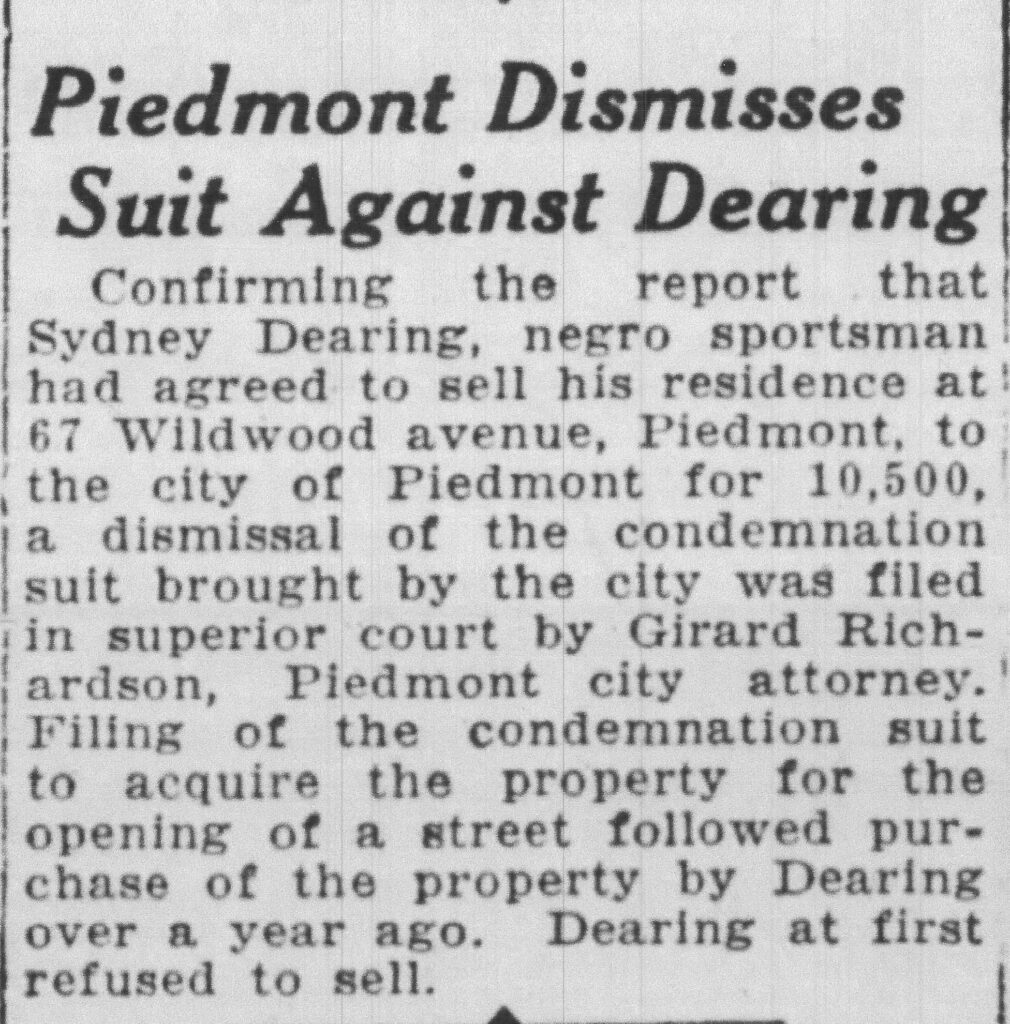

On January 29, 1925, the Oakland Tribune announced that the condemnation lawsuit had been settled out of court. Piedmont City Attorney Girard Richardson stated that a verbal agreement had been reached with Sidney Dearing and that the price had been agreed upon for the purchase of his house at 67 Wildwood Avenue. Dearing had agreed to sell his house for $10,500.

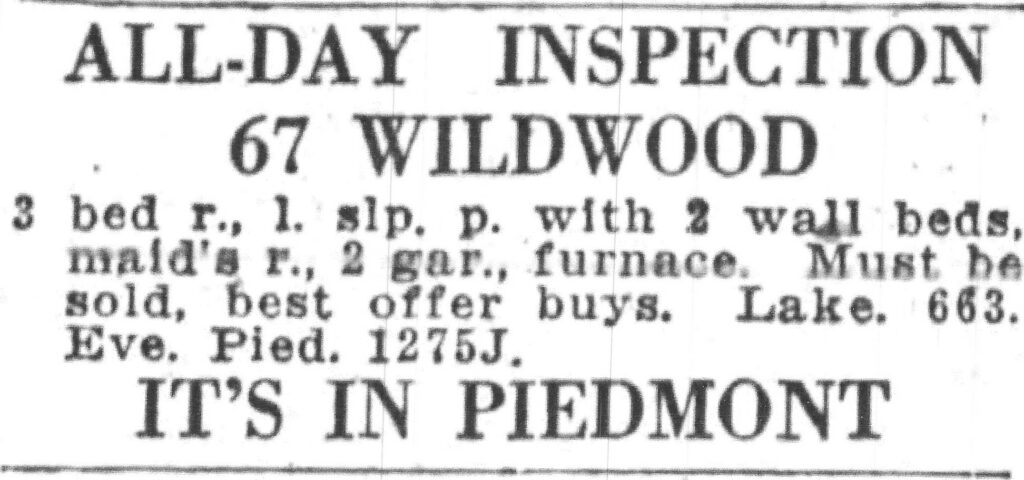

On May 3, 1925, the Oakland Tribune published a real estate ad for a house for sale at 67 Wildwood Avenue. “Must be sold. Best offer buys.”

Afterword

Sidney and Irene Dearing divorced in 1925, shortly after the city settled its lawsuit against Dearing. Sidney Dearing disappeared from newspaper headlines after he accepted the City of Piedmont’s offer to purchase his house and leave town. Irene Dearing moved to Manhattan, and in 1930 she worked as a telephone operator and lived with her two daughters, Thelma and Hilda, and her mother Julia Davis. Sidney Dearing died in Oakland on October 6, 1953, at the age of 83 and is buried in Alhambra Cemetery in Martinez, California.

The Sidney Dearing story was forgotten for many years. Queen of the Hills, once considered Piedmont’s only history, does not mention Dearing or his struggle as the first Black homeowner in Piedmont. Today, Evelyn Craig Pattiani’s Queen of the Hills is considered more of a memoir due to its omissions and inaccuracies.

Pattiani was 47 years old when Dearing was forced out of town. It’s likely that she knew of Dearing’s eviction. She was 77 when she wrote her book in 1954. As a member of a pioneer family, she told her history with pride and affection for her town. Did she forget Dearing, or did she choose to omit him from her history? I don’t know. Pattiani touched on racism when she described the action of schoolboys in the 1880s who threw stones at Chinese vendors as they carried baskets of fruits and vegetables from San Francisco to Oakland and the Piedmont hills, but she also described how valuable the Chinese were as “servants and cooks.” She later noted the city’s adoption of new ordinances that forbade dwellings of more than one unit, prohibiting apartments and flats.

Going Forward

The Dearing story was an ugly chapter in Piedmont’s history, but it sparked a new chapter in Piedmont. In the summer of 2020, residents and city officials learned of the city’s past racism and addressed social injustice.

On August 3, 2020, the Piedmont City Council passed a resolution officially acknowledging the racism of the past and resolved to “review City policies, ordinances, values, goals and missions through an anti-racism lens” and “committed to fostering a safe, inclusive and civil community.”

New community groups are addressing racial justice, each with a different focus. The Piedmont Racial Equity Campaign (PREC) is working with allied organizations and individuals to raise awareness about racism and support policies for racial justice and equity. The Piedmont Anti-Racism and & Diversity Committee (PADC) works to create opportunities to engage in meaningful change regarding issues of race and diversity and to advance the shared values of racial equity, diversity and inclusion. In March of 2020, a group of student leaders and faculty advisors revitalized the Black Student Union to give Black high school students a place to share their experiences.

Today’s residents and city officials are taking a proactive stance against racism and are moving toward fostering more equity and diversity throughout the city. By acknowledging and learning from past mistakes, the city is writing a better chapter in Piedmont’s history.

Gail G. Lombardi

Chair, Piedmont Historical Society